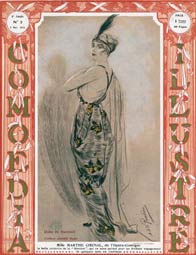

Fémina relate cette exposition dans son exemplaire du 15 avril avec plusieurs illustrations et La Gandara qui présente une robe dite Sévigné ; et dans Lecture pour Tous du 1er mai 1913, Armand Rio sous le titre ‘Les peintres costumiers de la mode’ relate : "C’est une innovation charmante : la mode, capricieuse et fantasque, vient d’appeler l’art à son aide. Désormais on peut espérer que les créations des grands couturiers seront exécutées des modèles fournis par des peintres célèbres. Ce sont les artistes eux-mêmes qui vont ici exposer à nos lectrices leurs idées sur ce gracieux sujet : les élégances de demain.

L’ Art français offre aujourd’hui à l’élégance et à la grâce des femmes le plus flatteur et le plus précieux des hommages. Pour concourir à la beauté de leur parure, un groupe d’artistes vient de se former sous la présidence de M. A. de la Gandara et de mettre l’art au service de la mode. Tous les mois, les ‘Peintres de la Femme’ exposeront chacun quatre modèles de toilettes, qui seront pour les élégantes les meilleurs conseillers du goût. Ils sont une douzaine. C’est donc, chaque année, plus de cinq cent toilettes, robes du soir et robes de ville, robes de bal et robes de sport, que créera la fantaisie de leur pinceau. La qualité de leur talent et la sûreté de leur art nous apporteront enfin la garantie dont le besoin se faisait sentir contre les erreurs de goût qui, en ces derniers temps, ont trop souvent offensé notre sentiment de la véritable élégance. (...)

L’ Art français offre aujourd’hui à l’élégance et à la grâce des femmes le plus flatteur et le plus précieux des hommages. Pour concourir à la beauté de leur parure, un groupe d’artistes vient de se former sous la présidence de M. A. de la Gandara et de mettre l’art au service de la mode. Tous les mois, les ‘Peintres de la Femme’ exposeront chacun quatre modèles de toilettes, qui seront pour les élégantes les meilleurs conseillers du goût. Ils sont une douzaine. C’est donc, chaque année, plus de cinq cent toilettes, robes du soir et robes de ville, robes de bal et robes de sport, que créera la fantaisie de leur pinceau. La qualité de leur talent et la sûreté de leur art nous apporteront enfin la garantie dont le besoin se faisait sentir contre les erreurs de goût qui, en ces derniers temps, ont trop souvent offensé notre sentiment de la véritable élégance. (...)

De tous les artistes, nul n’était plus désigné que M. A. de la Gandara pour présider cet aréopage de peintres, dont sera justiciable la mode de demain. On sait avec quelle incomparable virtuosité son oeuvre traduit l’élégance de la femme moderne. Le portrait de la Dame en rose au Luxembourg, celui de Mme Gabriele d’Annunzio à l’un des derniers Salons, témoignent d’un art consommé à rendre la souplesse transparente d’un voile et les nuances fugitives qui naissent et meurent aux plis d’une soie. Nous sommes allés lui demander de nous renseigner sur la tentative à laquelle il préside. (…) M. de la Gandara donne la dernière touche à un portrait de Melle Ida Rubinstein, qui se dresse avec la pureté de lignes d’une statue dans une gaine d’étoffe mauve.

‘Je suis ravi, nous dit-il, de la tentative que, mes camarades et moi, nous allons faire. Un peintre a, je crois, son mot à dire utilement quand il s’agit du dessin d’une robe et de son coloris. Révolutionner, créer du nouveau ? Non certes, nous n’avons pas cette prétention. D’abord, on ne crée pas, d’autorité, une mode nouvelle. La mode, c’est le produit de toute une époque, son reflet. Mais ce que nous pouvons faire, c’est la diriger, la corriger.

‘A chaque époque, la mode a eu son caractère et sa beauté. J’aime les robes grecques avec ces longs plis qui moulent le corps, mais j’aime aussi le XVIIe siècle, somptueux et magnifique, et Vélasquez a fait des chefs-d’œuvre avec d’immenses cages. Il y a eu pourtant, de-ci de-là, de lourdes fautes de goût que les artistes auraient eu le devoir de combattre. Voyons, n’auraient-ils pas dû, par exemple, s’insurger contre l’horrible, l’abominable ‘tournure’ dont s’affublèrent les femmes il y a vingt-cinq ans, et cela, en vérité, était-il tolérable?

‘A chaque époque, la mode a eu son caractère et sa beauté. J’aime les robes grecques avec ces longs plis qui moulent le corps, mais j’aime aussi le XVIIe siècle, somptueux et magnifique, et Vélasquez a fait des chefs-d’œuvre avec d’immenses cages. Il y a eu pourtant, de-ci de-là, de lourdes fautes de goût que les artistes auraient eu le devoir de combattre. Voyons, n’auraient-ils pas dû, par exemple, s’insurger contre l’horrible, l’abominable ‘tournure’ dont s’affublèrent les femmes il y a vingt-cinq ans, et cela, en vérité, était-il tolérable?

‘Pour ma part, je n’irai pas chercher mon inspiration dans le passé, quelque admiration que j’aie pour lui. Les modes d’autrefois sont mortes avec les êtres charmants qu’elles ont parés. Il ne faut rien rénover. Le costume féminin d’aujourd’hui a beaucoup de grâce et beaucoup de charme, même quand il est sportif. Un artiste peut trouver là tous les éléments du beau et faire un chef-d’œuvre d’élégance avec le dessin simple et pur d’une robe tailleur.

‘Bref, selon moi, notre rôle sera d’être de bons critiques soucieux de garder la beauté féminine, l’élégance de ses lignes. Quand la mode voudra y porter atteinte, nous serons là pour mettre le holà ! Dès que le snobisme exotique tentera de faire hurler les couleurs, nous protesterons!

‘Si nous pouvions, pour commencer, conclut en souriant M. de la Gandara, convaincre la femme moderne que l’armature rigide du corset, c’était bon sous Philippe IV, mais que la toilette d’aujourd’hui, souple et légère, exige la légèreté et la souplesse d’une ceinture ! Dites-le-lui donc de ma part ! ’

La révolte du bon goût ! Nous devions, en quittant M. de la Gandara, la trouver au seuil de chaque atelier."

Le retentissement de l’événement est significatif puisque cette initiative, annoncée dans une brève du Journal des débats politiques et littéraires du 11 février et reprise aux Etats-Unis lorsque le New-York Times du 9 mars 1913 annonce dans ses colonnes : "Famous Painters Form Society for Aiding French Dressmakers to Design Beautiful Fashions. In response to protests that have been made by French artists during the last year or two against the lowering of the standard of taste by the Paris couturiers, as shown by the introduction of the harem skirt and other eccentricities, the dressmakers have invited the painters to come to their aid.

An association of artists, consisting almost entirely of well-known painters who make a specialty of women's portraits, has been formed. It is called "Les Peintres de la Femme" and will act as a kind of advisory council in the development of new modes.

In an interview with a NEW YORK TIMES representative, the Marquis de la Gandara, who has accepted the presidency of the new society, explains in details the causes that have induced the painters to take this action.

The first fifteen members of the society include such well-known men as Willette, Gerbault, Albert Guillaume, Metivet, Nemnont, Anquetin, Roubille, Prejelan, and Abel Truchet. In response to their invitation, many other artists are giving their support to the movement. Marquis de la Gandara is one of the most successful of the French portrait painters and his work is always a feature of the Paris Salon.

"The so-called 'harem skirt' " said Marquis de la Gandara, "was really, I suppose, the origin of the rapprochement between the artists and the couturiers, which has taken shape in the form of the society we have called Les Peintres de la Femme. The reason for the name of course, is that most of us who belong to it devote ourselves to painting the portraits of women.

"The essential genius of 'le goût français' has always depended upon a strict adherence to the highest traditions of French art. The Paris dressmaker has been able to retain an envied position as the arbiter of feminine fashion because the artistic standards of the French nation have never been allowed to [ill.] below the point to which they were carried in the glorious past. The development of art in France, to an extent unequaled in any other country, has rendered this supremacy both natural and inevitable. In the rush and hurry of present day conditions, however, there has not been the same careful adherence to the highest traditions, to purity of design, to that unique standard of truth and beauty which have made French art what it is. Mistakes have been made. These have led to still further mistakes. The time has come for the artist to offer his services and to endeavor, apart from all commercialism and in the interest of art alone, to prevent the recurrence of such errors in the future.

"The essential error attaching to the introduction of the 'harem skirt' was the same as may be found in several other objectionable features in the modes of today : it was an anachronism, and consequently necessarily unbeautiful. not that the 'harem skirt' is inartistic in [ill.] example of the impossibility of reviving a former mode in anything like its original was shown perhaps last year in connection with the effort to introduce the panier.

"The panier, as many people will remember, never really got beyond the talking stage. It was seen at one or two of the race meetings, but merely as a balloon d'essai. Criticism proved too strong for it. The panier, in the form in which its revival was proposed, would have been as much an anachronism as the jupe culotte. It would have been utterly out of place in modern [ill.]. The broad doorways of that period no longer exist. Instead of driving about in the enormous family coaches that were used when this mode was general, women nowadays must be suitably attired to pass through the narrow doors of the automobile and the railway carriage. Considerations like these spoke the doom of the panier as our forefathers knew it, and the mode, when it ultimately came into vogue, had been modified to such an extent that it existed only as a sort of full drapery, and was therefore consistent with modern conditions, and as such free from most of the objections which would have met the panier in its original form.

"Why have these objectionable manifestations recently crept into our fashions. Well, that, I believe, is in one way a confirmation of what I was saying. Just now --- that the mode should always reflect and embody the spirit and the manners of the epoch. We are now in an epoch of extravagance and folly, of frivolity [ill.], of bold and striking enterprises, of abundant money and abundant luxury and display. Life with many people is full of excitement. Everything is noisy, high colored, and the day is rushed through at full-speed. The automobile and the aeroplane have impressed themselves so vividly on the consciousness of the nation that our whole life has been influenced by them to a much greater extent than most of us realize.

"The strenuous life, with its golf, its hockey, the whole programme of feminism, has made women more venturesome and daring, and particularly in regard to the style of their clothes. The graceful flowing robes of the past would be unsuitable in a period like ours, when women no longer sit at home, but are found, to thousands of cases, pursuing independent careers in life. Even the stay-at-home woman has been infected with the desire for greater freedom in her everyday life, and is apt to display her wider liberty nowadays as much in her choice of clothes as in anything.

"History, after all, is only repeating itself. In a former period of equal folly and recklessness women wore skirts which enabled them to display their limbs to an extremely liberal extent. There were the transparent robes, you will remember, of the ladies of the Directoire period, and the décolleté was the mode to a positively alarming extent. In the last year or two, we have had many indications of a sim [ill.] have no distinct inherited tendency or body of tradition. They live under the European system of civilization and they must necessarily draw all their ideas from Europe, because their instincts and development are almost entirely European. As things are, purely American modes would be without character or any real basis, and would express nothing. Perhaps in a thousand years but it is useless to discuss the suggestion. If the Americans seriously decide to adopt modes of their own, there will be only one description possible: they are not going to be dressed. They are going to be clothed.

"And the American woman! She is the best dressed in the world! In New York, I was astonished at the enormous number of women who paid the most careful attention to their clothes, regarded it as of the greatest importance, and succeeded in attaining the most perfect elegance. No woman attaches a greater importance to dress than the American woman, and none is more wonderful in the way she wears her clothes.

"Like the Parisiennes, the American women are very largely endowed with the instinct to dress well. Good taste cannot be attained by education – except, of course, to an exceedingly limited extent. It is almost entirely a matter of instinct. Many women, even wealthy ones, who can command the services of the most exclusive couturiers, dress in the worst possible taste, while numbers of women belonging to the poorest classes dress perfectly (…)"

Devant le succès de l’exposition parisienne chez Bulloz, le journal américain récidive le 4 mai : First Exhibition of Costumes Designed by Famous French Painters of Women's Portraits. "Paris, April 24.- The first showing of the new models of costumes designed by French painters who make a specialty of women's portraits took place yesterday at the Maison Bulloz. All designs were passed upon by a committee of the association of artists which calls itself "Les Peintres de la Femme".

The exhibition at the Maison Bulloz was in two sections. In one of the large salons were displayed the paintings send by the artists, while in the other apartments mannequins, dressed in costumes which were reproductions of the painted designs, posed and paraded. In an interview with the Paris representative of The Times, W. Gordon, manager of the Maison Bulloz, said: 'The artists have painted or designed styles for all ages of women, from the girl of 16 to the woman of 70, naming their creations Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter. Of course, there are dozens of other dresses also which have no age. The artists of these four seasons only wish to suggest to women how lovely they may be if robed in accordance with certain methods. The several models shown in the pictures were designed by La Gandara, Gerbault, Abel Truchet, and Willette. On paper the exquisite coloring is lost, and this constitutes one of their chief charms. The white evening dress, designed by La Gandara, for instance, with the beaded train outlines the form by accentuating its beauty. The only color used with the satin is king's blue, in the form of a high velvet ceinture which passes under the embroidery in front, while the butterfly bow in the back is of the same royal blue color, but in tulle illusion. Like nearly all the other dresses, this is appropriate for a woman of almost any age.

- White Evening Gown – The other white evening dress, which may be worn also at a dressy Summer afternoon function, is of cream supple taffetas, and was designed by Gerbault. The lace which forms two draped ruffles is blonde, and the ruffles or volants are edged in pearls. The draped ceinture is of the taffetas, falling in a big loose bow at the back. Like most of the best effects, the kimono sleeves form a fichu, and the lace shows off best when allowed to lie flat and soft against the form.

The evening or dinner gown, with train, by La Gandara, is sure to be a success, because of its graceful lines, to say nothing of the refined coloring. The foundation is of white crêpe de chine, with metal designs in lavender and gold. There is an underskirt of violet gaze de ninon, and the jacket effect, resembling the Russian blouse, is of the violet color, of mousseline, rimmed in rhinestones. The buckles of black complete a fine color scheme. This robe, like all the best ones, narrows at the knees, to branch out above and below.' (…)"

L’exposition à la maison Bulloz fut inaugurée par Alfred Massé, ministre du commerce, de l’industrie, des postes et des télégraphes accompagné de M. Bolley, directeur des affaires commerciales et industrielles, qui eurent l’occasion de féliciter Antonio de La Gandara pour les présentations de maquettes et cette application directe de l’art à l’industrie. Même madame Raymond Poincaré s’invita à l’exposition qui se renouvela en novembre à la maison Buzenet.

L’éclairage ainsi organisé sur le design du vêtement féminin déclencha une enquête de la revue La Mode du Temps, laquelle publia une lettre de La Gandara le 20 décembre 1913 : " On m'a souvent demandé ce que je penserais, le cas échéant, de la suppression du corset. Je me suis borné à répondre que l'heure n'en était point encore venue. Cette heure est-elle venue ? Oui ? Eh bien ne regrettons pas L'abolition du corset puisque, selon La Bruyère, il y a plus d'affectation à négliger la mode qu'à la suivre.

Il faut bien se rendre compte, du reste, que les femmes et les artistes n'inspirent pas la mode comme on l'a dit. Ils sont au contraire ses esclaves volontaires et dociles. Il faut être de son temps, puisque le nu lui-même affecte un style différent aux diverses grandes époques de l'art. Un nu du Primatice et un de Boucher sont deux choses très différentes. Du moment que le corps féminin sans voile suit la mode, pourquoi voudrait-on qu'habillée la femme la dédaignât ? Toutes les époques eurent leur charme et je regarde avec autant d'émotion artistique une infante de Velasquez que l'impératrice de Winterhalter.

Il sera charmant de se priver du corset, mais les gaines Louis XV en corne d'abondance étaient aussi fort jolies. Toutes les modes sont exquises, puériles, divines, grotesques et charmantes. Acceptons-les comme elles nous viennent et aimons-les assez pour ignorer pourquoi! Antonio De La Gandara."

Les peintres costumiers de la mode

En 1913, Antonio de La Gandara fonde avec plusieurs artistes peintres une association chargée de promouvoir la mode française. Il s’agit d’Abel Truchet, Jules Grün, Louis Anquetin, Lucien Métivet, Albert Guillaume, Henry Gerbault, Adolphe Willette, Maurice Neumont, Auguste Roubille, René Préjelan.

L’ambition de ce groupe dont il prend la présidence et de mettre le talent des peintres de la femme au service du savoir français que l’on a pu voir s’égarer dans un étrange afflux d’éléments venus de loin, extérieurs à l’esthétique de notre race, descendus du théâtre dans la ville et remontés de l’Orient à l’Occident. Cette belle initiative a immédiatement séduit la 'maison Bulloz', qui a demandé à ce comité de participer à une exposition avec croquis, dessins et aquarelles dans ses salons du 140 avenue des Champs Elysées en avril de cette même année.