1894, 20th Mai

"Notable pictures by American and French masters.(…) Passing now from home art to Europe, we find almost a beautiful companion to Whistler's masterpiece [Montesquiou's portrait], and this is Gandara's portrait of the Princesse de Chimay, née Ward. The lady has the reputation of being the most beautiful woman in Paris. Her hair is now golden, in contrast to raven eyelashes, and her imperial profile is majestic. The way the artist has painted her flesh tints is like some delicate shell work. She stands in a flowing, clinging Empire robe of white satin, the short baby waist embroidered in gold. One arm gracefully gathers a long silken gauze scarf, which the other hand just touches. It seems to float from her shoulders, as the dress appears both to cover and show her limbs. She is at once modestly draped and almost nude. Her disdainful head is thrown back; she breathes, and is certainly the most living portrait I have ever seen. As the passing crowd put it, she looks the Empress ready to command, and meaning to be obeyed."

1897, 4th Dec.

"Antonio de la Gandara, who is soon to have an exhibition of his works at the Durand-Ruel Galleries in this city, is of Spanish descent on the paternal side. He became deeply impressed in childhood with the drawing and coloring of the masters of that school – Velasquez, Zurbaran, etc. He has, moreover, very original ideas upon art, distinguishing – without, however, separating – the impressions of art which give birth to conception, and the execution of these impressions, which is, says he, the technical part of the profession. Following out this order of ideas, it is sufficient for a true artist to catch, if only for a moment, a glimpse of a pretty woman who is dressed with taste to have her image impressed on the brain like a kaleidoscope, and then on the canvas under the influence of a kind of special retrospective vision. It is by these means that de la Gandara has been able to enrich French art with some beautiful pictures.

He was born in Paris in 1862, and was a pupil of the Beaux Arts, where he studied under Gérôme from 1876 – when he was fourteen years old – to 1881. He exhibited for the first time in 1883 at the Salon, Champs-Elysées, a picture called 'St. Sebastian Pierced with Arrows' which gained for him honorable mention and a great success in the artistic world. In 1892 he exhibited in the Champ de Mars various portraits, among others, those of the Comtesse de Montebello and the sons of the Vicomtesse de Pierredon. The same year de la Gandara exhibited at the Durand-Ruel Galleries in Paris with renowned success several other portraits, notably those of the Comtesse de Greffulhe, Mme de Montebello, the Prince de Sagan, the Prince de Polignac, the Princess de Caraman-Chimay with her son in her arms, the Prince de Borghese, count Robert de Montesquiou, Paderewski, Prince Wolkonski etc. He has also become known through his series of

He was born in Paris in 1862, and was a pupil of the Beaux Arts, where he studied under Gérôme from 1876 – when he was fourteen years old – to 1881. He exhibited for the first time in 1883 at the Salon, Champs-Elysées, a picture called 'St. Sebastian Pierced with Arrows' which gained for him honorable mention and a great success in the artistic world. In 1892 he exhibited in the Champ de Mars various portraits, among others, those of the Comtesse de Montebello and the sons of the Vicomtesse de Pierredon. The same year de la Gandara exhibited at the Durand-Ruel Galleries in Paris with renowned success several other portraits, notably those of the Comtesse de Greffulhe, Mme de Montebello, the Prince de Sagan, the Prince de Polignac, the Princess de Caraman-Chimay with her son in her arms, the Prince de Borghese, count Robert de Montesquiou, Paderewski, Prince Wolkonski etc. He has also become known through his series of pastels, entitled 'Night Effects on the Boulevard".

pastels, entitled 'Night Effects on the Boulevard".

Two large portraits in oils from his brush have made a sensation, 'The Lady in Green', shown at the Salon of 1893, and his 'Portrait of the Princess de Chimay' which was exhibited in Brussels and London. His portrait of Sarah Bernhardt, exhibited in 1895 at the Champ de Mars, also gained for him high praise. He exhibited in the Salon at the Champ de Mars in 1896 three portraits of women and a 'Corner of the Tuileries'.

At the Universal exhibition in 1889 the artist obtained a bronze medal; he was decorated with the Order of Isabella, the Catholic in 1889, and was nominated Chevalier of the Legion of Honor in 1893. He obtained the gold medal at the Munich Exposition in 1897."

1897, 11th Dec.

"The art season, after a long season of inaction, opened with a rush on Monday last, and there have been several exhibitions of various kinds which have kept the members of the art world busy all during the week. Perhaps the most interesting displays have been those of portraits by Jean Boldini and Antonio de la Gandera [sic], both noted Parisian portrait painters. (…)

At the Durand-Ruel Galleries, at Fifth Avenue and Thirty-sixth Street, there are now on exhibition six portraits by Antonio de la Gandara. All are women, whom this young Spanish artist loves best to paint, and one, that of Sarah Bernhardt, exhibited at the Salon of 1895, won as much praise as his better known portrait of the 'Princess de  Chimay', which is unfortunately not shown here. The six portraits now displayed are all life-size and painted full-length. The artist either selects tall women to paint, or makes his subjects taller that they are in reality. He delights in long and graceful lines, quiet colors and effective, if simple, poses. To view his work after an hour with Boldini is like stepping out of a fireworks display into the stillness and quiet of a winter night. Boldini is all fire and glow in subject, execution, and color. De la Gandara is subdued, quiet, and more refined. While Boldini is unquestionably the more powerful artist, de la Gandara's works have a charm, even if less brilliant, that those of the former do not possess. The most notable of the portraits which are now shown are those of Sarah Bernhardt and the celebrated Mme. Gauthereau, who was the reigning beauty in Paris during the administration of Jules Grévy, and who was a New Orleans creole, a Miss Avignon [sic]. The history of her family is a romantic one, but space will not permit its description here. The lady, who has a wealth of reddish hair and an interesting and remarkable face, is shown with her back turn to the spectator and her head turned so as to show her long and striking profile. Her hair is dressed in a Psyche knot, and her dress, one of clinging white satin, is cut sensationally low, and showing most generously her beautiful molded arms, neck and shoulders. In her right hand she holds a large grey feather fan pointed forward, the

Chimay', which is unfortunately not shown here. The six portraits now displayed are all life-size and painted full-length. The artist either selects tall women to paint, or makes his subjects taller that they are in reality. He delights in long and graceful lines, quiet colors and effective, if simple, poses. To view his work after an hour with Boldini is like stepping out of a fireworks display into the stillness and quiet of a winter night. Boldini is all fire and glow in subject, execution, and color. De la Gandara is subdued, quiet, and more refined. While Boldini is unquestionably the more powerful artist, de la Gandara's works have a charm, even if less brilliant, that those of the former do not possess. The most notable of the portraits which are now shown are those of Sarah Bernhardt and the celebrated Mme. Gauthereau, who was the reigning beauty in Paris during the administration of Jules Grévy, and who was a New Orleans creole, a Miss Avignon [sic]. The history of her family is a romantic one, but space will not permit its description here. The lady, who has a wealth of reddish hair and an interesting and remarkable face, is shown with her back turn to the spectator and her head turned so as to show her long and striking profile. Her hair is dressed in a Psyche knot, and her dress, one of clinging white satin, is cut sensationally low, and showing most generously her beautiful molded arms, neck and shoulders. In her right hand she holds a large grey feather fan pointed forward, the arm being curved like a swan's neck. Mr. John S. Sargent painted the same subject in 1884 and used something of the same pose. Sarah Bernhardt has also been painted with her back to the spectator and her face turned upward in profile, and is also clothed in white satin with big sleeves. The lines of the figure are extremely graceful. The portrait of Mme. Klotz, who is gowned in a pink opera cloak and a ball dress, is charming in tone and has beautiful modeling of neck and shoulders. The portrait of Mme. Salvator is chiefly notable for its easy, graceful pose and piquancy of expression. The painting of the texture of Mme. Beer's gown is remarkably fine. The portrait of Miss Robertson, gowned in pale yellow, although attractive in color and very simple in pose, is the least successful of the portraits. The flesh color is somewhat chalky. It is hard to place de la Gandara. While his work is reminiscent of other well-known portrait painters, he still holds a place peculiarly his own. His portrait shows much study, good method, and on the whole an excellent sense of color, but perhaps the qualities of refinement and appreciation of the temperament and atmosphere of the women of the Haute [sic] Monde are its most striking characteristics."

arm being curved like a swan's neck. Mr. John S. Sargent painted the same subject in 1884 and used something of the same pose. Sarah Bernhardt has also been painted with her back to the spectator and her face turned upward in profile, and is also clothed in white satin with big sleeves. The lines of the figure are extremely graceful. The portrait of Mme. Klotz, who is gowned in a pink opera cloak and a ball dress, is charming in tone and has beautiful modeling of neck and shoulders. The portrait of Mme. Salvator is chiefly notable for its easy, graceful pose and piquancy of expression. The painting of the texture of Mme. Beer's gown is remarkably fine. The portrait of Miss Robertson, gowned in pale yellow, although attractive in color and very simple in pose, is the least successful of the portraits. The flesh color is somewhat chalky. It is hard to place de la Gandara. While his work is reminiscent of other well-known portrait painters, he still holds a place peculiarly his own. His portrait shows much study, good method, and on the whole an excellent sense of color, but perhaps the qualities of refinement and appreciation of the temperament and atmosphere of the women of the Haute [sic] Monde are its most striking characteristics."

1898, 1st Jan.

"Holiday week has been unusually dull in the art world of New York this year. There have been no pictures of any particular note to be seen in the dealers' galleries, and the only exhibitions open have been those of portraits by Boldini, at the Boussod-Valadon; by de la Gandara, at the Durand-Ruel; and Cecilia Beaux, at the American Art."

1898, 22nd Jan.

"(…) Mr. de la Gandara, who is now in New York busy with the execution of several portrait orders, has added to his portraits now on exhibition at the Durand-Ruel Gallery a portrait of Mr. Haines. This, the first portrait of a man that the artist has shown in New York, has more life and is somewhat richer in color than his portraits of women, which have already been noticed in the New York Times. The pose of the head is a little awkward, but the figure has life and movement, is natural, and, above all, is painted with rare refinement. It is to be hoped that Mr. de la Gandara will show us more portraits of men before he leaves New York, for this canvas gives evidence that he may be more acceptable as a painter of men than of women – good and thoroughly artistic as his women portraits are.(…)

It is particularly interesting and instructive to compare and study them [the works of several American painters mentioned earlier in the article] in conjunction with the near-by dramatic and forceful portraits of Boldini and the thinly and cold colored but essentially artistic, portraits of de la Gandara. If one may use a somewhat unromantic simile, it may be said that if Boldini's canvases represent the highly seasoned and spiced condiments of a feast, and de la Gandara's the cold side dishes, Madrazo's may be compared to the deliberately tinted ices and confections of the end of the dinner."

1898, 19th March

"The young Spanish-French portrait painter Antonio de la Gandara has just completed a portrait of Mrs. Burke-Roche, formerly Miss Fannie Work, which is now on exhibition in the Durand-Ruel Galleries. The portrait is the most satisfactory that Mr. de la Gandara has shown here. He has, as his custom, painted Mrs. Burke-Roche standing, or, rather, as if posing while walking across the room. The picture is full length, with the head fully turned toward the front. There is a sense of arrested movement in the canvas, and the lines of the figure just indicated under the simply made and close fitting white satin evening dress are very graceful. The background is a rich one of dark brown, suggesting mahogany, and the artist has produced a charming effect by the introduction of a veil of soft tulle, which drapes the front of the figure and flows backward. Very artistic in effect also is the delicate shoulder band of pearls, which holds the bodice up, and on which there is a glint of light. The likeliness is admirable, and the portrait, with much refinement, has a warmth lacking in the artist's other portraits of women shown here."

1898, 23rd Jan.

1898, 23rd Jan.

De Kay, Charles

"The success of Mr. Chartran in painting portraits over here has been heard of in France and several other French painters have resolved that he shall not be alone to gather the spoil from les rastaquouères of America and from the ordinary millionaires of New York. Among the crop of adventurers this winter, the young Spanish-Frenchman Gandara is remarkable for the individuality of his style, as well as for the prominence of his sitters in one or other of the social realms.

Mr. Antonio de la Gandara was born of a Spanish father and a French mother about thirty-five years ago in the city of Paris. He took to the study of art early in his teens, worked at the Beaux Arts School under Gérôme, and in 1883 obtained an honorable mention for a St. Sebastian at the Salon. This beginning was conventional enough, not did the bronze medal he obtained in 1889 at the Universal Exposition lead one to await anything very noteworthy from him. But since then a change has come; he is no longer the same Gandara he was.

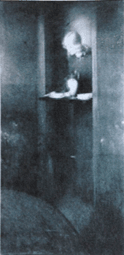

At the exhibition in Dresden last year were several paintings that called attention to the rather meagre French section. There was a slender Puritanic handmaiden or Quakeress, with severe, comely face and sternly brushed hair, issuing from a dark doorway with a tray covered with porcelain tea things in her hand. She was odd yet graceful; she made you pose and admire; there was a mystery in the very dark background and a something unusual yet not quite unfamiliar in the girl – what was it ? James Tissot of Paris and later of London? Or, back of Tissot, the suggestion of Burne-Jones? At any rate, it was not at all French, nor Spanish, nor Italian, nor German.

At the exhibition in Dresden last year were several paintings that called attention to the rather meagre French section. There was a slender Puritanic handmaiden or Quakeress, with severe, comely face and sternly brushed hair, issuing from a dark doorway with a tray covered with porcelain tea things in her hand. She was odd yet graceful; she made you pose and admire; there was a mystery in the very dark background and a something unusual yet not quite unfamiliar in the girl – what was it ? James Tissot of Paris and later of London? Or, back of Tissot, the suggestion of Burne-Jones? At any rate, it was not at all French, nor Spanish, nor Italian, nor German.

And at Munich last Summer the same painter had pictures which won for him a gold medal. So one sees that he has been finding his native city too small for his ambitions. Scorning French Chauvinism, he has dared to exhibit his works in Germany: and now Europe itself is too narrow; he must try a flight across the Atlantic to the land of fellow-artists he has known so well before and since leaving the Beaux Arts. What has he more to win at home? Is he not decorated with the Order of Isabella the Catholic, whatever that may signify, and with the medal of Chevalier of the Legion of Honor? Aside from the pictures bought at misery prices by the French Government, the greater part of those which are really sold at all are bought by American amateurs or by dealers for the American market. No wonder that the United States is the Eldorado of the modern painter.

Mr. de la Gandara has been since 1892 a steady exhibitor at the Salons of the Champ de Mars. In that year he had a separate showing of pictures at the Durand-Ruel Galleries, where the number of his portraits was only equaled by the high sounding titles owned and sported by many of the sitters. Among them was a likeness of the fastidious literary dilettante Count Robert de Montesquiou-Fezensac, and a portrait of the only Paderewski, not to speak of mere ordinary princes, such as Sagan, Polignac, and Wolkonski. With such achievements behind him, there can be no doubt that the good American who loves to be painted by the man who limned princes will step up and order at once his portrait, or rather, the portrait of his wife or daughter.

Mr. de la Gandara has been since 1892 a steady exhibitor at the Salons of the Champ de Mars. In that year he had a separate showing of pictures at the Durand-Ruel Galleries, where the number of his portraits was only equaled by the high sounding titles owned and sported by many of the sitters. Among them was a likeness of the fastidious literary dilettante Count Robert de Montesquiou-Fezensac, and a portrait of the only Paderewski, not to speak of mere ordinary princes, such as Sagan, Polignac, and Wolkonski. With such achievements behind him, there can be no doubt that the good American who loves to be painted by the man who limned princes will step up and order at once his portrait, or rather, the portrait of his wife or daughter.

The only drawback to this is th e method of Mr. de la Gandara's workmanship which is extremely conscientious and very slow. He does not dash off a portrait at one sitting, nor at three, nor at five. One must have a great store of patience if one sits to Mr. de la Gandara. But what would you? Good things are not wrought in a hurry. Often the dashing portrait fails to hold its own when the first pleasure in its cleverness has passed while earnest thought put into the slowly wrought one tells in the long run. His method seems to be to paint a figure with the utmost definitiveness and sharpness, as if it were by Gérôme himself, and then submit it to such changes and to subdue the less important details in order to give to the chief lines and masses the prominence he desires.

Take, for example, the portrait of Mme. Gautreau figured here. The dress itself is of the plainest, but its cut is startling, being such as to show the lady's very beautiful back and the chaste modeling of her shoulders. The hair is drawn off the brow and tied so that the fine shape of the head is seen. The skirt fits close, and more than hints at the form beneath; its lower lengths fall in great folds, which give the lines of an inverted morning glory. The lady seems to have advanced and then stepped back, looking pensively at her big feather fan, but showing plainly by her calculated pose that she is aware that people are observing her, yet avoiding at the same time any expression of anxiety as to what their opinion may be.

It was bold of Mr. de la Gandara to paint Mme Gautreau, because she has become in a certain way a test for painters, ever since Sargent made her likeness and was attacked because he showed her shapely shoulders adorned by nothing more than a strap. Others followed, making the lady now a rousse, and again a yellow blonde, but ever a somewhat severe yet subtle profile withal. Both face and figure are worthy of the strongest artistic hands. Mme. Sarah Bernhardt, too, has been painted on canvas almost as often as she has been painted for the stage. De la Gandara has suppressed in this case the heaviness that advancing years lend the features by painting the famous actress from behind, with her head slightly turned to the left. Here again are the long sweeping lines of the skirt, exaggerated so as to give great height to the figure and at the same time to suggest movement away from the spectator. The portrait of Mme Salvator is more like those of other artists; more care is given to details of the dress, such as the black lace on the shoulders and the feathers in the big hat. The color scheme is carried out by the lips and the red rose the lady is fastening in her belt. In this case the hands are somewhat clawlike, and have been painted so colorless as hardly to suggest flesh.

It is a pity that Mr. de la Gandara has not exhibited some of his genre pictures, for they go far to explain a peculiar something in his workmanship which may worry and perplex observers. His simplicity of treatment is indeed far from simple, it is rather veiled, rather indirect, one might almost hazard the word unfrank. It may be said of this painter's work in portraiture, as of the work of many modern artists, that it extorts admiration for its undeniable cleverness – which is not, be it noted, a flashy or flippant tricky cleverness – but does not hold one's affection."

RETOUR A « CRITIQUES »